(Image: Chris Dlugosz/Flickr)

(Image: Chris Dlugosz/Flickr)

ABOVE THE MANTLEPIECE IN THE living room of Janette Fennell’s home, there’s a painting in whites and pinks and sweeping blues and yellows. At the center, an angel is holding a baby. Behind her, two others hover. And then, there, in the bottom right corner, are two small, human figures. In contrast to the soft strokes of the rest of the painting, straight lines trap them in a small, squat box. They’re crouched inside, squished together, one person’s head at either end.

“Here we are, in the trunk,” Fennell explains. “That’s my husband, and that’s me. That’s where our hearts would be.” She points to the soft yellow dot glowing inside each figure. “This picture is representative of what happened to us.”

Almost 20 years ago, Fennell and her husband Greig were kidnapped from their garage, in the trunk of their own car. Left alone, still trapped, in a dark park in the south of San Francisco, they escaped. In the wake of that crime, Fennell has been working to make sure that no one dies trapped in a car and, in the process, has changed the way people in America drive.

Packing for a trunk release (Image: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

Packing for a trunk release (Image: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

On October 29th 1995, when she was shoved into the trunk of the family Lexus, Fennell was 41 and had just had her first baby. Before her son was born, she had worked for Eastman Kodak for more than a decade and, later, for the beauty products company Helene Curtis. “I was a fast-tracker, really dedicated, really workaholic,” she says. For Kodak, she had moved 10 times across the country: every one of those moves meant a promotion, and, she says, “When you get into that corporate environment, everybody wants the next job. So I was happy to be chosen.”

But on this Saturday night, she had spent the past nine months working only as a new mom and, on weekends, teaching at her church’s Sunday school. The family had been over a friend’s house for dinner, and since Halloween was just a few days away, the baby was wearing, she remembers, an outfit that featured a black cat popping out of a pumpkin.* As they pulled into the garage, just before midnight, she was thinking that she still needed to prepare her lesson for the next day.

As the garage door closed, two men rolled underneath, on their sides, like a dog might. They were wearing Halloween masks, one a grimacing werewolf, and they got on their feet, put guns to Janette and Greig’s heads, and ordered them into the trunk. The two men tried to slammed the lid down, but the Fennells were sharing space with the baby’s travel gear. They had to get out, unload, and stuff themselves back in.

Alex was still in his carseat, and, now closed into the trunk, the Fennells heard one of the two men say, “There’s a baby.”

That was it. The car backed out of the garage and started moving through the streets of San Francisco. They did not know what the two men had done with their son.

In the trunk, Janette, closer to the bumper, whispered, “Can you hear him? Can you hear him?” She had heard on Oprah that if you were kidnapped and didn’t escape within five minutes, you were dead. More than five minutes had already passed. She could tell they were heading south through the city, and she thought: they’re going to take us to L.A., or Mexico…She and Greig were both praying. Nothing made sense.

As the car moved through the city streets and then onto the highway, Janette started pulling on the carpeting in the trunk. She didn’t know why, exactly. But she was able to expose a bunch of wires, and she was pulling at them. The weight of two adults in the backseat had the car bottoming out on the city streets, and she thought that if she could make the lights flicker or flash, maybe someone would see it, maybe they would call 911, maybe the car would be pulled over, and they would yell until someone heard and freed them.

But that didn’t happen.

They left the highway. They left paved roads. And then the car stopped. The trunk lid popped open. Janette tried to poke her head out, and one of the men hit her in the head with the butt of his gun. They wanted cash. They wanted jewelry. They wanted bank cards and pin numbers. They had the Fennells repeat the code five times over, and they said that if it wasn’t right they would come back, and they would kill them. And then they left.

When she and Greig were alone, Janette felt calm, she says. The two men had the right pin number, and they were gone. The trunk was totally black.

And then—this the part she calls the “woo woo” part—Janette saw a little light in the area where she had ripped out all the wires. Greig didn’t see the light. But it was shining on the little piece of wire. The words, Janette says now, came from her mouth but not from her brain.

“I think I found the trunk release.”

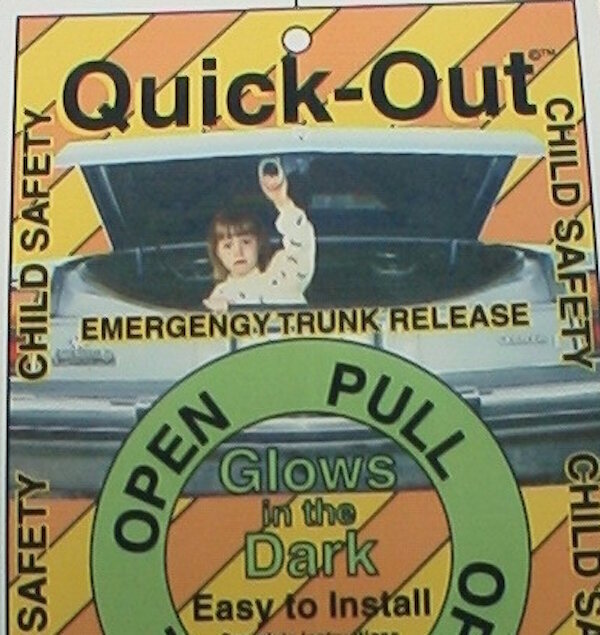

The San Francisco Chronicle, October 30, 1995 (Image: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

The San Francisco Chronicle, October 30, 1995 (Image: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

In the painting in the living room, the baby in the angel’s arms is Alex. After Janette had guided Greig’s hands to that piece of wire, after he had pulled it and unlatched the trunk, after she had soared out of that trunk and back into the world, Janette first dashed to the backseat. There was no baby there.

They found an emergency key and found their way back to the city. They called 911 from a payphone in a dicey neighborhood, and while a car of undercover cops showed up immediately, followed by uniformed officers, they had to wait for the dispatcher to send a policeman to their house to hear, finally, that the baby was safe. The masked men had taken him out of the car, still in his carseat, and left him sitting outside the house.

He was fine. In the photo that appeared that Monday in the San Francisco Chronicle, he’s smiling cherubically, his eye bright blue and his hand reaching towards the camera. Fennell’s in the background, her blond hair feathered into ’90s bangs, putting a borrowed car seat into a rented car. A police officer had told her the night before that usually, these stories didn’t end so well. She could imagine all sorts of crazy things, but one question, she says, kept playing over and over, like a tape in her head: How does it end? How does it end? How does it end?

“I know it sounds silly but I can tell you, without any reservation, that after this happened, I got a fax from God,” she says. “He said, Ok, I spared you and your family, and I’ve also given you talents. You can figure this out: now go out there and change it.” She laughs. “Our minister said to us: ‘I’ve heard of very different ways of people communicating with the Lord. I have never heard of anyone who got a fax.’ But that’s the way it was.”

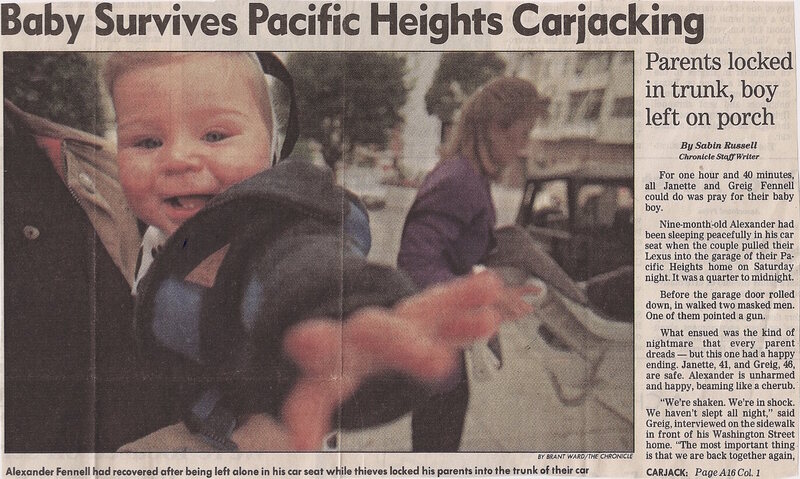

The Fennell family (Photo: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

The Fennell family (Photo: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

She started by learning how these cases usually end. She’d comb through the results of wide-ranging, pre-Google internet searches and pick out cases of trunk entrapment to add to a hand-made database. She found out how these cases sometimes do end—brutally, with rape, drowning, or the car being set on fire. She started writing to car companies and working her way through federal government bureaucracies, showing them her database of hundreds of cases, and not getting particularly far.

By the summer of 1998, though, she had made an ally of then-Representative Bart Stupak (D-Mich.). They had met through a series of introductions, and Stupak, who had been a police officer and state trooper earlier in his career, understood the issue. For his first efforts to pass regulations, he “got a lot of grief” from automakers, he said at the time, but he was able to pass a provision requiring a closer look at the problem. Congress had directed the federal agency responsible for traffic safety to study the possible benefits of equipping cars with a device that would internally release the trunk lid. An expert panel was recruited to study the issue.

But before the first meeting, the issue became national news; that summer in just three weeks’ time, 11 kids died of overheating, while trapped in trunks.

Even with that background, though, when the agency’s expert panel of advocates, medical and safety experts, and car manufacturers met that fall, it wasn’t certain that the panel would recommend that an internal trunk release be required. In the second of three meetings, the panel discussed options, including letting car manufacturers install releases voluntarily. At the third meeting, Fennell remembers, “They were all backing down at the last minute.” She pointed out that the group she had founded, Trunk Releases Urgently Needed Coalition, had been working with states to pass similar regulations. So, she told the manufacturers, they could just send different kinds of cars to every state in the union.

“We won by one vote,” she says.

Even before the final regulation made the change mandatory, though, Ford began putting trunk releases in all their vehicles. The company invited Fennell to come to the auto show where they’d announce the change. After the announcement, a photographer asked her: Would you be willing to get in the trunk of the car and demonstrate it?

Not everyone who’d gone through the sort of traumatic experience that Fennell had would have agreed. But, she says, “I”m in sales and marketing. I know how those things go.”

In the picture, her legs are tucked behind her and one arm scrunched beneath. Her right arm is reaching upwards, to show the glow-in-the-dark, T-shaped pull that would be standard from then on.

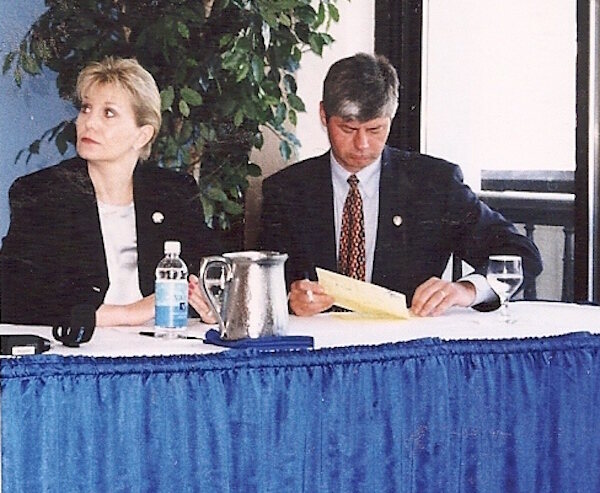

Fennell and Rep. Stupak at a conference in 1999 (Image: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

Fennell and Rep. Stupak at a conference in 1999 (Image: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

Today, Fennell works out of her house in the Main Line, just a short ride from Philadelphia, with two rescue dogs, one large and fluffy, the other smaller and shyer, as company. Alex, now in college, plays Division I tennis, and her second son, Noah, is still in high school. In the living room, along with the angel painting, are framed copies of the bill Fennell most recently helped pass through Congress; her office is decorated with copies of news articles telling her story. On a bench, there’s a collection of toddler-sized stuffed animals, part of a campaign she’s currently working on, to keep kids from dying of heat stroke while trapped in hot cars.

After winning the regulation on internal trunk releases, Fennell thought she was done. But while she was working to push that through, she had heard from parents of kids who had died in other ways, too. Once again, she started collecting data. Even 15 years ago, many of the cases she found dealt with heat stroke. But soon she saw two spikes: kids being strangled by power windows and kids being run over by cars that had been knocked into gear. She started a new group, Kids and Car Safety, and expanded the issues she worked on to “non-traffic” incidents, that happen off public roads and highways.

In past decade and a half, Fennell’s work on these safety issues has changed the way that cars work in small but vital ways. In cars that are made today, the switches that control power windows, that automatically roll up, require a finger to scoop them upwards, so that no kids can accidentally activate one while leaning on the door. It’s now required that cars can be put into gear only when the driver has a foot on the brake, so that the car won’t start rolling backwards without warning. And within the next few years, every new car will be required to have a rear view camera that actually shows what’s behind a reversing car.

Each of these tiny changes, though, is a battle of its own. The rule to put in rearview technology, for instance, was first required in a safety bill passed in 2008, the Cameron Gulbransen Kids Transportation Safety Act. (It’s named after a two-year-old whose father backed over him in the driveway.) The Department of Transportation had three years from the date of the law’s enactment to publish final standards, and in 2010 a proposed rule would have mandated a rear-view camera for all vehicles, with a phase-in period ending in 2014. But by 2014, the final rule was still being delayed. “I remember Ray LaHood,” the former Secretary of Transportation, “saying: You’ll just have to be patient,” Fennell says. But she had been patient. Her group, along with Public Citizen and other advocacy organizations, prepared to challenge the DOT in court over its delays. The day before the hearing was scheduled, the department issue the final rule. The deadline for automakers to install the cameras is now 2018.

These hard-fought changes might be small, but they also make a huge difference. “We have not been able to uncover one case of a person dying in a trunk since those releases were put in,” she says. “We have plenty of stories of people getting put in the trunk by a thief, and taken to the ATM. But they found the release and jumped out.”

Not everyone would have turned a narrow escape into this sort of crusade. After she and Greig were trapped in the trunk, people would always reassure Fennell that she didn’t have to talk about it. But she says, talking about it helped. “The way that I was able to heal was talking about it and warning other people,” she says.

The Fennells actually kept the Lexus that they were trapped in for years after the incident. (The locks were changed.) “It’s a great car!” she says. “We only had one, and we didn’t put many miles on it, so we kept it.” But when they were finally ready to be rid of it, Fennell called a friend at Toyota who had offered once to buy it. The company sent a huge truck to their house to take it away, and put it in the Toyota museum—the car from which internal trunk releases were born.

Not long ago, Fennell and Alex were in Southern California, for a tennis tournament, and they went to visit the car in the museum. Alex, Fennell says, got in the car.

“So this is the car where it all happened,” he said.

“I stood on one side, and he stood on the other side, and we put our hands on the roof,” Fennell remembers. “My friend took a picture. It was really fun.”

Janette Fennell today (Photo: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)

Janette Fennell today (Photo: Courtesy of Janette Fennell)