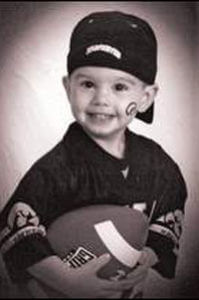

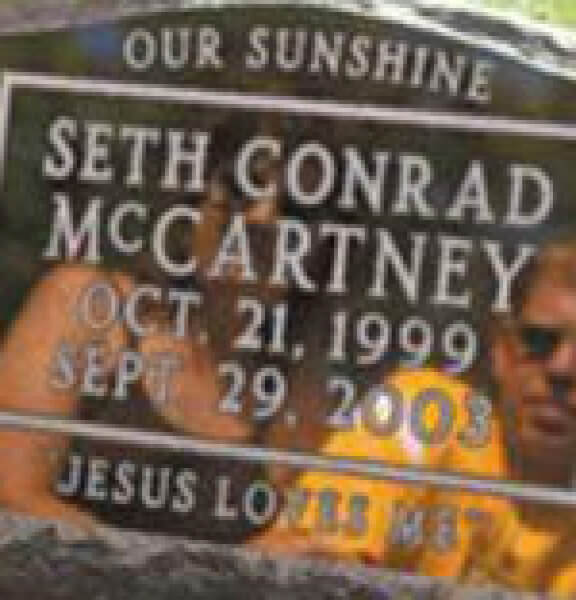

Seth McCartney

October 21, 1999 - September 29, 2003

Child’s death creates living nightmare for parents

Father says ‘please forgive me’

De Soto, Ia. – Outside, in the yard, a sheet covered Seth’s body. Inside, the 3-year-old’s siblings huddled in a bedroom, crying and praying. Deputies asked all the necessary questions as the forgotten chicken-and-macaroni casserole dried out in the oven.

Marc McCartney, his jeans dirty from kneeling beside his son, turned to Stephanie, his wife of 10 years.

“” Please forgive me.””

Just a few hours before, Marc McCartney had backed a Bobcat skid loader into their youngest son.

Seth McCartney died Sept. 29, 2003, after an afternoon of “”helping”” his dad, two older brothers and younger sister with landscaping work around their recently constructed home outside De Soto. It started as a happy, sunny fall day.

After their dad deposited piles of landscaping rock with the skid loader – a compact machine used on farms and in construction – the children would help move the rock into place with a toy shovel, toy rake and wheelbarrow.

Everything changed shortly after 5:30 p.m. that day when they were quitting for supper, just as Stephanie and Seth’s older sister were arriving home from piano lessons.

It was 5-year-old Samuel’s scream that first told Marc McCartney he hadn’t just backed into a toy wheelbarrow. It was a sound that stopped his mom as she was about to go inside.

Much later, Samuel would say that his little brother Seth had been pushing the little red wheelbarrow, just looking up at the sky.

Seth wasn’t watching the skid loader. And his dad didn’t see his youngest boy as he put the nearly two-ton machine in reverse.

In a hundred ways, the raw journey that Marc and Stephanie McCartney had begun as they collapsed beside their son’s crumpled body would be like that of other parents who lose a child so early, so unexpectedly.

Yet when a parent or other relative is the driver in an accident that kills a child, their immediate role is infinitely more difficult to set aside than in a drowning or other tragedy. Guilt can become a haunting presence.

SPECIAL TO THE REGISTER

Seth

Many Deaths

Last year, more than 100 children younger than 15 were killed in the United States when they were backed into by vehicles on private property, according to Kids and Cars, a Kansas-based child-safety organization that has built a database to track such deaths. The actual number could be two or three times higher, said Janette Fennell, the group’s president and founder. Legislation signed into law Wednesday by President Bush will require the federal government to begin counting these incidents on private property, and also will require research into preventing such accidents.

At least three children in Iowa have died this year when they were backed over. A grandmother in Ely hit her 6-year-old grandson; a mother in Hawarden hit her 2-year-old son; and a man in Muscatine hit a 2-year-old boy.

Fennell has noted an upward trend in the fatalities in recent years, which she attributes to the popularity of vehicles with larger rear blind spots, such as minivans, pickups and sport utility vehicles. More than 60 percent of the known incidents since 1998 involved these types of vehicles.

“” And in over 70 percent of these cases, the mom or dad or another relative of the child was the driver,”” Fennell said.

Accidents

The known number of children killed nationally and in Iowa each year in back-overs on private property:

2005: 62 nationwide as of July 22; three so far in Iowa.

2004: 101 nationwide; two in Iowa.

2003: 92 nationwide; one in Iowa:

2002: 71 nationwide; none known in Iowa.

2001: 52 nationwide; none known in Iowa.

Source: Kids and Cars

The burden of being the driver in such a tragedy must be recognized and understood quickly before it combines with the grief of losing a child and tears apart those still living, destroying a marriage, a family.teacher last year. It was titled “”The Day my Brother went to Heaven.””

I saw that my brother Seth had been run over by the skid loader. I ran to see if he was OK. When I went to see if he was OK, I knew he wasn’t OK. When I saw that I started to cry. I cried very very hard. I could not stop crying. When my mom and dad told me to go pray, I ran inside and started praying.

Marc, kneeling over his son, knew, through his grief and shock, that his four other children had already seen too much that afternoon, especially the boys. Take them inside, Marc had urged Stephanie. She hurried her other children inside and asked them to pray for Dad while, in the yard, Marc sobbed, carefully placing his own body over that of his young son.

Marc was, illogically, he knows, trying to keep the boy warm. Trying to protect Sethy, who hated the wind in his face, from the brisk breeze that stirred up the fresh dirt that still surrounded their new home.

He was telling his boy he was sorry.

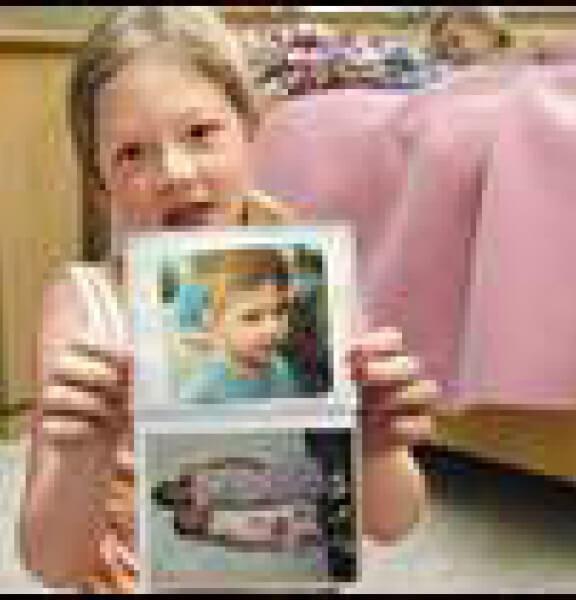

Frozen in time: Faith McCartney, 9, holds a picture that she took of her 3-year-old brother Seth before his death in 2003.

Forging ahead together

Often-used statistics describe divorce rates among couples who lose a child of anywhere from 50 percent to 90 percent. Recent studies have shown, however, that those statistics appear to be more myth than fact. The divorce rate instead appears to fall in the range of 9 percent to 12 percent.

Still, few would dispute that a child’s death can be hard on a marriage.

Rod Whitney, a close friend from Westchester Evangelical Free Church who was among the first people the McCartneys called after Seth died, arrived that night and found Marc, who was going into shock.

Marc had discovered when he’d tried to dial his parents’ farmhouse in Hubbard that his hands were numb and tingling. He was hyperventilating, a paramedic told him. Stephanie remembers seeing him breathing into a paper bag. Whitney had worried that Seth’s death would pull Marc and Stephanie apart. So he was relieved when, within a short time of his arrival, Stephanie came to him with a request. “”I remember Stephanie a couple times pulling me aside . . . and saying, ‘You need to make sure Marc cannot blame himself. This was an accident,’ “” Whitney said.

How to cope If your child dies:

• Expect initially to feel shock, numbness, denial and disbelief. Over time other emotions emerge, such as guilt, anger, loneliness, sadness and regret.

• Learn to express and share any feelings of guilt, especially with other bereaved parents. These feelings are normal and talking through them will help you learn to forgive yourself.

• Sleep deprivation is common, but can add to a feeling that you are “”losing it.””

• Avoid the use of alcohol or drugs in hope the pain will go away. Use prescription medicine sparingly and with a physician’s. supervision

• Hold off on major decisions, such as career changes or moves. By moving, you may lose your support system when you need it most.

• Don’t be rushed by others to take steps to move on, such as cleaning out a child’s room

•Make sure that your surviving children aren’t “”forgotten”” and that they understand this is a shared family experience. Include them in family plans and decisions. Be frank with them and your spouse.

• Get support as you begin the new life without your child. Accept offered help to give yourself time to grieve.

Source: The Compassionate Friend

“” It stuck in my head because it just seemed so amazing that she was concerned about him right then.””

Still, Stephanie couldn’t stop thinking about Seth lying in the yard. She’d been back outside once, had kissed her son’s cheek and told him, as she had hundreds of times before, that she loved him. But now, she repeatedly asked the deputies and medics whether someone was with him. She couldn’t stand the idea of him being alone. She also ached to hold him, something the damage to his body made physically impossible. Whitney remembers a deputy being understanding and telling Stephanie he’d see what he could do.

Together, Marc and Stephanie went outside into the now-darkening evening to see their son one last time before his body was taken away. Marc held Seth’s foot; Stephanie held his hand. They cried. They talked to Seth. They prayed outside with Whitney and perhaps a dozen other friends who had arrived as the evening turned colder.

Unexpected decisions The day after he accidentally backed into and killed his 3-year-old son, Marc McCartney sat down to write: Did not sleep night before. Terrible, horrible thoughts and pictures running through my mind. Marc had tossed and turned that September night two years ago, reliving Seth’s death over and over.

The next morning marked the start to Marc and Stephanie McCartney’s life without the second-youngest of their five children. “”You’ve got to pick out the casket and the vault, and the whole time we were feeling like, ‘What are you talking about?’ “” Marc remembers. “”It was just horrible.”” It was the times when the couple left their home to choose a cemetery plot or take Seth’s favorite stuffed animal to the funeral home that it would hit them how the rest of the world was moving on when theirs had come to a halt. “”You cannot imagine the feeling,”” Marc said. “”You drive a car next to someone else and think, ‘They have no idea what I’m doing right now.’ “” One motorist saw the McCartneys’ SVNHWKS license plate when the couple was out that day and drove by slowly as a passenger held up his University of Michigan shirt to taunt the University of Iowa fans. Stephanie, who at the time was holding in her lap the burgundy striped shirt, tan pants and dress shoes in which Seth would be buried, thought, “”He’s thinking of the big game next weekend, and we’re going to plan our son’s funeral.””

A child’s funeral:

It was the next day that the two saw Seth’s body again, this time at the funeral home in a child-sized white coffin. Tucked in Seth’s arms was the stuffed squirrel he had always taken to bed. They placed his Hawkeye hat on his head, glad the boy they had last seen lying in the dirt behind the skid loader looked more like himself. Marc and Stephanie, alone in the room, lingered over their son’s body, holding hands and talking to one another about their son, about the funeral. Then, without warning, Marc dropped Stephanie’s hand. “”I just need a minute.”” He placed his hand on the side of Seth’s casket. Then he broke down. Tears ran down his face. He asked his son once again to forgive him. He told him he loved him. “”I think this was the moment that God helped to release Marc from his feelings of guilt,”” Stephanie would later write in her journal. Looking back, Marc knows Seth’s death was an accident – they’d warned the kids about staying far from the skid loader when it was running – but that didn’t make it easier. “”I knew it was an accident . . . but you can’t take away what I had done,”” he said.

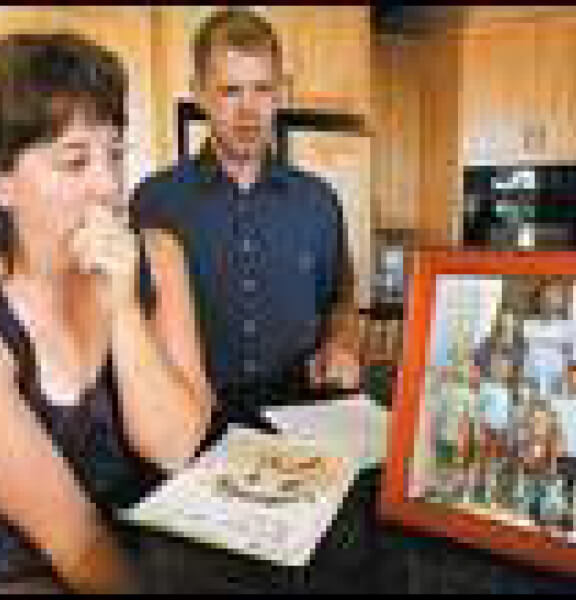

Mementos:

Stephanie and Marc McCartney coped together after their son Seth, 3, was killed in 2003 by a skid loader driven by Marc. Shown above is a picture of their family before Seth died. The following day, the Rev. Don Long offered these thoughts to those who crowded into Westchester Evangelical Free Church in Des Moines for the funeral: “”We are people that love to control things, yet the Bible talks about how the Lord has numbered our days.”” People can’t control the number of days they have on Earth, Long said, but “”what we can control is how well we choose to live the days that we are given.”” Marc and Stephanie invested well in the more than 1,000 days they had with Seth, Long told the crowd. That message helped solidify in the rural De Soto couple’s mind a way of thinking of their time with Seth. “”We focused a lot ourselves on the idea that he was on loan to us,”” Stephanie said. Learning a new life It wouldn’t mean that learning to live without Seth at their side would be easy. The weeks passed slowly, and each new event without Seth presented another agonizing obstacle. They asked Marc’s father to take and sell the skid loader, wanting that reminder to be gone. “”You wouldn’t believe how many things happen back-to-back that are firsts. It’s constant,”” Marc said. “”His birthday, Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day. Even the first time we went out to eat as a family was hard.””

Looking back, Marc knows Seth’s death was an accident – they’d warned the kids about staying far from the skid loader when it was running – but that didn’t make it easier. “”I knew it was an accident . . . but you can’t take away what I had done,”” he said.

The following day, the Rev. Don Long offered these thoughts to those who crowded into Westchester Evangelical Free Church in Des Moines for the funeral: “”We are people that love to control things, yet the Bible talks about how the Lord has numbered our days.””

Deaths in Iowa Children killed in back-overs on private property, according to Kids and Cars: 2005:

Zachary Ryan, 6, in Ely on April 17;

Christian Topete, 2, in Hawarden on April 23;

Ricardo Berry, 2, in Muscatine on May 30. 2004:

Galilea Cardenas, 2, Columbus Junction, May 8;

Lindsay Brewster, 18 months, in Elvira on Sept. 26. 2003:

Seth McCartney, 3, in DeSoto on Sept. 29.

Five days after Seth died, Marc spent the afternoon cutting the grass on the family’s acreage. From atop the lawn mower, Marc had watched his other sons, Elijah and Samuel, ride their bicycles. “”I just suddenly had this feeling that everything was going to be OK, that things can be happy again one day.”” As the months slowly passed, Marc became the one who pushed Stephanie to make herself face all those “”firsts.”” He persuaded her to decorate for Christmas and write a Christmas letter when she didn’t feel like it. He persuaded her to get the annual group photo of the children taken when she knew it would only emphasize that one of her children was missing. “”We were also trying not to suck the joy out of the lives of our other kids,”” Stephanie said. “”They kept us smiling and laughing and reminding us that we have to keep doing those things.”” Stephanie McCartney, so soon after that first Christmas without Seth and during the bleak first months of 2004, though, was battling her own feelings of guilt for not being able to save Seth. She also struggled because she couldn’t remember having told Seth she loved him on the day he died.

She described in her journal a dream she had one winter night early in 2004: I heard a noise in the TV room and when I entered the kids’ pillows. were in a stack and playing amongst them was Seth. He was wearing his red and blue Star Wars pajamas. I immediately fell to my knees and started crying and saying, “”I can’t believe that God sent you back to me.”” Seth immediately got up and gave me one of his cute, adorable smiles with those big brown eyes. He put his forehead against mine and then we wrapped our arms around each other. We hugged and I told Seth that, “”I love you,”” and he told me that he loved me too. Then, abruptly, Stephanie woke up. She was in her bed. Seth was still gone.

But there was something else, something left behind by the dream besides the almost-real sensation of holding Seth in her arms. “”I felt a huge release from my burden.””

It was one of many small steps that Stephanie and Marc McCartney would take over nearly two years to hold themselves together.

“” There’s no question that when a child dies in a family that the family dynamics are changed and will be forever,”” said Wayne Loder of The Compassionate Friends, a group for those dealing with the death of a child. “”When there is an empty seat at the dinner table, you never forget that.”” ‘I’ll go to Heaven’ Linda Bauer, Stephanie’s mother, watched first with worry, then with pride as she saw how Marc and Stephanie handled themselves. “”My first concern, without knowing how they were going to react for sure, was would they blame each other?”” Bauer said. But “”they’ve got it together.””

Perhaps there was one memory of Seth that carried this couple and their other children through more trials than any other memory, gave them more comfort than any other.

It was late on the night that Seth died when Stephanie first recalled the incident. It had happened no more than a few weeks earlier. Stephanie, Seth and the youngest, Grace, were in the Suburban, having just dropped Samuel off at preschool.

From his booster seat in the back, Seth piped up: “”Mom, when will I go to Heaven?””

Stephanie smiled. “”Not one second before Jesus is ready for you.””

“”When will he be ready for me?”” Seth asked.

“” Not for a very long time.””

Later, after they picked Samuel up from preschool, Seth excitedly told his 5-year-old brother what he’d learned. “”When Jesus is ready for me, I’ll go to Heaven,”” Seth happily told his brother. Stephanie remembers being pleased that he had listened.

And then Seth added: “”But I think he is ready for me now.””

It is that remark that leaves Stephanie wondering now.

She thinks about Samuel’s explanation of why Sethy didn’t see the skid loader that September afternoon when he died.

He wasn’t paying attention to where he was going, Samuel had said.

He was just looking up at the sky as he pushed the toy wheelbarrow.

But there were no trees, no tall buildings to catch a small boy’s attention.

Perhaps a bird was flying overhead. Maybe there was an airplane. Or a funny-looking cloud.

But Stephanie McCartney thinks back to Seth’s own voice in the Suburban and can’t help but wonder if her little boy was looking for something else in the sky.

“”I’m convinced he was seeing Jesus coming.”””

Donate in Honor of Seth