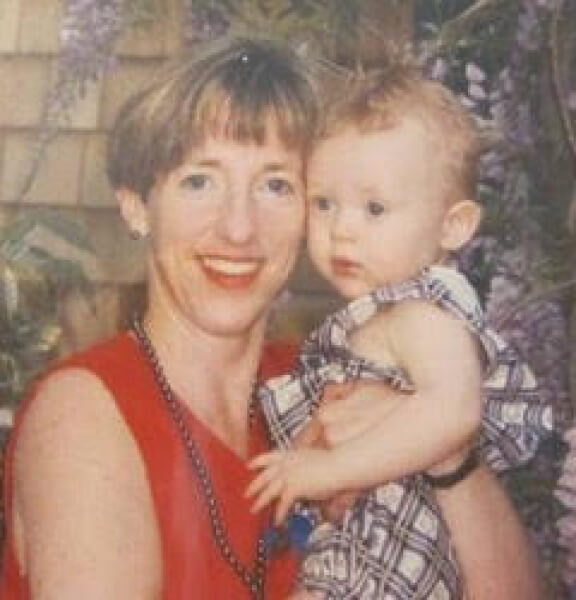

Noah Kittel

May 18, 1996 - August 10, 1997

August 10, 2017 marked the twentieth anniversary of the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day when our 15-month–old son, Noah, was run over in my in-law’s driveway by my 16-year-old niece and died. And because life does, somehow, go on, and because I’ve not yet successfully eliminated cars from my life, I spent that day driving from our home in RI to the airport in Boston with my husband and our youngest child to bid adieu to two of our children departing on a three-week hiking adventure in Germany and Yugoslavia. I might have preferred to gather my flock beneath my wing or at least within sight and spend the day hiking together, which we did manage to do with the three oldest of our five living children for the tenth anniversary of their baby brother’s death. But our oldest daughter was at work in her home city of Washington, DC and our oldest son was hiking around Easter Island far, far away. So that left us trying to treat the day like any other as the three of us left behind sat beside colorful flower boxes in an open-air restaurant in the North End toasting our children, near and far.

I tried to be fully present as we dined on homemade pasta, but the truth is that a part of me will always live in the past. Because that is the time when I lived with Noah. And because of fetal maternal microchimerism, which means that the cells from my son are likely still swimming around in my own body, as mine were in his as he went to his grave, a part of me will forever remain in that driveway, crushed beneath the wheel of a green Chevy Tahoe.

On May 14, 2014, my first book, a memoir entitled Breathe, was published, parts of which are excerpted here for this particular telling of Noah’s story. I always knew that someday I’d write a book. But, like most of you who will take the time to read this here, I certainly never dreamed that life would hand me this particular tale to tell. And given all the many blessings life has handed me in the days and decades since, I’d trade it all if I could have my old life, the one that included Noah in it, back.

On May 18, 1996, I sat alone in my hospital room recovering from the long night of labor and the early morning delivery of our second son while my husband went with the nurse to give our fourth child his first bath.

“We need to decide on a name,” I said to Andy when he returned and snuggled in next to me. “It’s the first line item on every one of these forms.” I loved words, and naming my babies was one of my favorite parts of having them. “Obviously, Emma is out.”

But before I could give voice to the boys’ names we’d considered, Andy said, “Well, while we were bathing him, he looked at me with a wisdom that seemed greater than his age. With his reddish hair and that look, I knew—he’s a Noah.”

I eyeballed my baby, sleeping beside us in his Plexiglas bin, and said “Noah” out loud a few times, feeling it in my throat like a breath of fresh air. I’d always liked the story from Genesis about Noah and the Ark—all those animals rocking side-by-side in a boat made from gopher wood. Two by two, I thought to myself as Noah completed our family pattern of two girls, two boys.

I’ve lived near one ocean or another all of my life, and I spent the summers of my childhood floating over Atlantic waves on my back with my ears underwater, all sounds erased except my own thoughts. I’d watch the herring gulls circling beneath the clouds overhead and listen to the sounds of that ancient flood that drowned the rest of the earth’s creatures. How lucky I felt to be held so easily by that salty element.

“Okay. Let’s call him Noah. Noah Patrick.” I said, adding Andy’s middle name.

“Noah Patrick Moore,” we recited, expanding the name to include my own maiden name, a practice we began when our first son, Micah, was born. And so it was that Noah Patrick Moore Kittel was named conclusively after God’s chosen one, reminding us of God’s promise to preserve life. And although the rain had fallen steadily for forty days and forty nights that spring, on that May day, the sun finally shone on Oregon—just like in the scriptures—while our newly expanded family floated along in our ark, two by two, singing, “Rise and shine and give God your glory.”

Noah was ours to have and to hold for 15 months. Not even close to nearly long enough, by our standards, but what a lovely life he lived. His three siblings and his parents adored him. He was the first baby I had who gazed at me with blue eyes matching my own as I nursed him from the morning of his birth until the morning of his death. Noah had one of every holiday and one happy birthday, a brief sample of all that life promised, all that could have been. If. Only.

In this great nation of ours, 50 children are backed over by a car every single week because a driver couldn’t see them. The accident is described based on which direction the car is moving, resulting in front-overs or back-overs.

Noah happened to be on the side of the car next to the driver’s tire, so his would technically be categorized as a side-over. This “side blind zone” is currently being recognized as more of a problem than originally thought.

Back-overs mainly take place in driveways and parking lots and in over 70% of these tragedies, the driver is a parent or close relative like Noah’s cousin.

Over 60% of back-overs involve a larger vehicle like a truck, van, or SUV similar to the Tahoe that she was driving. And the predominant age of back-over victims is one-years-old, somewhere between 12 and 23 months old, a toddler, like Noah, who has just learned to walk and is happily exploring the world around them. This newfound freedom leads to an average of 232 deaths and 13,000 injuries every year from back-overs. But even one is too many. Especially when that one is your own beloved blue-eyed son.

Sunday, August 10, 1997 dawned on the Oregon coast where we were spending the weekend at Andy’s parent’s farm. The house was full of family so we’d been sent up the driveway to sleep with our kids in the creepy cabin they sometimes rented out to people down on their luck. As usual, Noah was the first one awake that morning and he stood up and grinned at us from over the rail of his porta-crib squeezed in at the foot of our bed, wanting to climb in with us but unable to get his leg over the edge.

“Baba,” Noah said. “Ba Ba.”

Andy sat up and reached his long arms to meet Noah’s, pulling him into bed between us. Noah snuggled in and closed his eyes in contentment. While he nursed he kept pushing Andy’s face away from him with his hand. “Hey, I want Mommy, too,” Andy said, laughing and teasing him. Having never woken up in that room before, I looked around me in the new light, trying to change my mind about it. But it smelled musty and was not improved by closer examination. I was relieved that we’d soon be leaving it.

The other three kids woke up, got dressed, and ran down the driveway to the main house. The hens had had chicks and they were so excited to get to the barn to play with the fluffy, peeping balls. I got up and picked out Noah’s clothes for the day: his denim overalls, his Noah’s ark T-shirt that my mom had given him for his birthday, and his lime-green saltwater sandals. I tossed them all to Andy and sat on the bed. I loved watching Andy’s big hands wrestle Noah’s little clothes onto his toddler’s body and tickle and play with him. I could have sat there all day, watching them giggle together.

All was well in the present tense of our world. Andy and I loved each other and our four children. We had good jobs and a big loving family. The sun smiled on us, and the morning beckoned with its fingers-crossed promise of another lovely day to follow. Andy clipped Noah’s binky onto his overalls, and Noah popped it in his mouth as we headed out to the sunshine and down the driveway into the day that would change all days to follow.

***

“Oh, I like your cute sandals, Noah,” Cody said after breakfast. I pulled him out from the high chair where he’d finished eating one of my homemade blueberry muffins and some Cheerios, most of which now littered the floor. He looked down at his feet and stomped them a few times, slipping on the Cheerios and the shiny Formica floor while showing off both his sandals and his newfound agility. He grinned like the star of the show, so pleased with himself.

The coffee pot was emptied and refilled a few times, and Cody started cleaning out the china hutch which occupied the entire dining room wall opposite the table, piling jumbled treasures from the large, cluttered cabinet—plates, cups, saucers, photos, and assorted knickknacks—on the floor. It reminded me of what she’d done at Mildred’s house, and I knew once she got started, she wouldn’t stop until the cabinet was empty of all things she deemed junk. Marcella was a Depression-era hoarder, so this immediately set her on edge. “Now why are you doing that?” she asked as her treasures stacked up all around. “Now don’t you throw anything away,” she said, watching Cody’s every move like a hawk while Cody carried on, ignoring her.

Noah was also watching his aunt, attracted to all the shiny and breakable things emerging from the depths of the cupboard and wanting to touch them all. Cody grew frustrated with him, and he with her constantly snatching everything away from him, so I decided to put him down for his morning nap. Rather than hang out in that creepy cabin while Noah slept, I asked Andy to get his porta-crib and set it up in the back bedroom where we’d be sleeping that night. Leaving Noah in the house, I walked outside with Andy and watched him head between the parked cars and up the driveway, stopping on his way to pet Dude, who was lying down on the other side in the shade. The air was heating up, and it looked like it would be another perfect day, but suddenly I felt so tired, like all the energy had just been sucked right out of me.

Micah and Christiana ran up and asked, “Can we go with Cally, Mom?”

“My mom said I can take the kids to the beach,” Cally said as she walked out of the mudroom door behind me and into the carport. She was proud of her driver’s license, which was only a few months old.

I hadn’t really formulated a plan for the day and was thinking maybe I needed to lie down with Noah, too. “I guess that would be okay,” I said. The foot-numbing cold of the ocean meant the kids wouldn’t be swimming, and I thought they’d have fun splashing around in the stream we’d played in the day before, which would be easy enough for Cally to handle.

“Okay,” I said, thinking I should go inside and get their beach toys.

Micah’s red life jacket hung on the clothesline out back, drying from our river swim the evening before, and as I walked back toward the door I heard him calling, “Mom, Mom, get this, get this.” I could see him across the backyard, jumping up and down, trying to reach the jacket and pull it off the line.

“You don’t need your life jacket,” I said, walking across the grass to him.

“Yes I do, yes I do!” he said, his frustration threatening to escalate into a temper tantrum.

“All right,” I relented, fetching it off the line just so he would stop. “You don’t need this,” I said, wondering why on earth he wanted his life jacket for the beach. I held on to it while we walked across the yard and through the back door into the mudroom to get their toys, crossing to the windows that lined both front walls and overlooked the driveway.

Still arguing with Micah, I happened to look up and out the window and noticed Cally playing with the stereo in the driver’s seat of Cody’s green Tahoe, which was parked right outside the windows. I glanced back down toward Micah to continue the life jacket debate when a sudden movement caught my eye. I looked out the window again and saw Chane jump out the back door of the Tahoe on the passenger’s side, the side nearest to me. I saw her look behind the car and jump back in. I was still wondering why she’d done that when my eyes traveled around to the front of the car, where I noticed what looked like Noah’s shadow by the driver’s side front tire. Is that Noah? Is he standing on the other side—the side I can’t see?

I stood riveted in the mudroom, holding Micah’s red life jacket while he pulled at my side yelling, “Mommy,” as if now from a great distance away.

And then I realized that the car was running.

And I saw Cally start to reverse, turning the front tires sharply to the right to back the vehicle around.

And I saw what Chane had not seen when she looked behind the car.

And I saw what Cally would have seen if she had looked out her window.

And I saw what someone in a smaller car would have been able to see from closer to the ground.

And I saw what Dude could see from his spot across the driveway in the shade.

I saw the shadow of one small sun-kissed boy with little green sandals who loved cars and trucks.

And then I saw first his shadow and then my son disappearing under the left front tire of that five-thousand-pound vehicle.

“STOP, Cally, STOP!” I screamed from inside the house, through the double-paned windows and the walls that I couldn’t burst through—the door was miles away down the hall behind me.

“STOP!”

“STOP!”

My breath was wasted. I was completely powerless to stop her. I could not move from that spot. I could not put two thoughts together or make two muscles move to wrench myself into motion and reach my baby in time. I could not save my son. And she did not stop. She kept going.

So I stopped. I stopped breathing. I stopped watching.

And the world changed.

Behind all that summer sunshine, darkness had been lurking. Now I saw it. I saw it clearly. And I could never again pretend it didn’t exist.

I ran out of the house, through the carport, and picked up my sweet still boy in his dusty overalls and Noah’s ark T-shirt. He was not bloody. He was not moving. I crushed him to my chest, wondering too late if maybe I shouldn’t have moved him in case he had a neck or spine injury. I ran into the house with him as fast as I could, through the mudroom and into the kitchen, where I stopped, summoning the courage to extend my arms so I could look at my baby. He still wasn’t moving. I felt a sickening wave wash over me.

You’re about to collapse, my brain managed to say to my body.

Just then, Cody appeared at my side, and I quickly handed Noah to her, putting my hands on my knees and doubling over—trying to get some blood flowing, trying to breathe while the life was sucked right out of me.

“Oh, God,” I said, turning to look at her.

“His head,” Cody said. She held him at arm’s length, then turned and ran outside with Noah in her arms. I straightened up and followed, briefly wondering where she was going and catching up to her at the bottom of the back steps, where she handed Noah back to me and simply said, “Oh, Kelly.”

And just then Noah touched my arm with his left hand. “Mommy,” his tiny voice groaned from somewhere already far away.

Cody and I looked at each other and sprang into action, trying to save Noah’s life with the life-saving skills we’d learned, trying to do this one thing together. I laid him on the grass and Cody started CPR; she did the chest compressions while I gave him mouth-to-mouth.

Cally ran into the house behind us, saying, “Now everyone will hate me!” Andy had appeared outside behind us but he quickly turned away. I found out later that he had followed Cally inside to call 911, but in the moment I wondered where he was going, thinking he was following her—and thinking, We’ll deal with the living later.

Soon I realized that Bud and Buster had materialized and that the kids had all gathered around us and were watching. Even in the midst of performing CPR, I searched my mothering mind to think of something for them to do. In between breaths I said to my poor crying kids and their cousins, “Hold hands! Hold hands and pray!”

Then Noah groaned again. He threw up. Cody rolled him on his side and I watched the blueberry muffin I’d fed him for breakfast dribble into the grass along with the breast milk he’d woken up to that morning. I tried to believe he was coming around and resumed making my desperate attempts to breathe for him, praying all the while, Breathe, Noah, breathe, breathe, damn it, please, God, make him breathe!

After what seemed like forever, an ambulance siren filled the air, adding a welcome cacophony to our quiet counting and compressions. The family circle was split in two by the paramedics who appeared by our sides and took over. In one swift motion they sliced that little Noah’s ark T-shirt right down the middle—a decisive, destructive act that shocked me to my core. I clutched at my own chest, catapulted into the gravity of our situation, where all things we might have considered precious before, like preserving a cute first birthday gift from Grandma, were shredded. They strapped Noah onto a body board much too big for him and lifted him up in a well-rehearsed choreography. I didn’t know how they could possibly move with the weight of all the hope I had piled on their shoulders. But they did, carrying Noah to the ambulance in a practiced rush, with me in desperate pursuit.

“Ma’am, you can’t come with us,” one of them said as they passed Noah through the door.

“I’m a trained first responder,” I replied, trying on Cody’s boldness for size. One look at my eyes told them that I was going, and there was no time to waste arguing. I jumped in, they shut the door behind me, and our siren shattered the peaceful prayers of every church service we passed that Sunday morning.

Once we were underway, the medics jabbed a long needle into Noah’s leg. I held his hand and stroked his arm like I always did when he got a shot. But he didn’t even flinch.

“Look at him,” I said to nobody in particular. Noah always cried when the doctor gave him a shot. “He doesn’t even care,” I murmured. Usually I’d have tried to quiet him down; now I desperately wanted him to scream and cry and hold his arms out to me and to bother everyone. But he was being such a terribly good little boy. The ideal patient. The paramedic looked at me with her professionally neutral eyes and said nothing, which spoke volumes.

The emergency system had been activated, and the 911 operator had radioed the ambulance to meet the Life Flight helicopter down the coast at a grassy airstrip called Wakonda Beach Airport, from where Noah would be flown to a Portland hospital—his only chance at survival. Andy was

following somewhere behind us in the sheriff’s car. But while the ambulance rushed westward, there was a change of plans—it was not, after all, another perfect day. That damned summer fog had returned, smothering the coast like a wet blanket. The visibility kept shifting, making it impossible for a helicopter to land, so we received instructions to go north to Newport Hospital instead, where the Life Flight team would meet us. With our sudden change in direction, Andy and the sheriff lost us, and at the Newport Hospital I found myself alone with Noah and the emergency medical system in action. They wheeled him out of the ambulance and into the emergency room and shunted me off to the admitting desk to fill out paperwork.

“You can have a seat here in the waiting room,” the desk lady informed me.

My body trembled, but I steadied my gaze, channeled Cody, and said, “There’s no way in hell I’m going to sit in the waiting room and read magazines while my baby is in there fighting for his life.”

She conferred with a nurse, who capitulated. “You can come in as long as you remain quiet and stay out of the way.”

Just then Andy arrived, so they escorted us both to Noah’s room. As we entered, they were receiving another update from Life Flight: now the fog was too thick for them to land at Newport; they were forced to land seven miles inland in Toledo, and Noah would have to be transferred yet again by ambulance. All of this was wasting precious time. Noah’s life was ticking away. Our son’s life depended on the fickleness of fog.

As the fog rolled in and out, Andy and I stood against the wall at Noah’s feet, watching helplessly while the doctors resuscitated our baby two or three times. We held hands silently, desperately, and prayed. On the wall next to Noah’s bed was a backlit X-ray of his head. His skull was cracked in three places. I could only glance at it, not wanting to commit this picture to memory.

The doctor asked to speak with us privately, and we followed him to his office, reluctant to leave Noah. He said, “I need you to understand that your son has sustained a severe head injury. It’s your decision whether or not to send him to Portland.”

I couldn’t accept that they might not be able to put Noah back together again, even though this was no nursery rhyme. I looked at Andy and he looked at me and neither one of us needed to say a word. “Send him,” we said without a moment’s hesitation.

“Okay, well, then you might want to say good-bye,” the doctor said. There was no room in the helicopter for any passengers. But that wasn’t the kind of good-bye he meant.

Andy and I did what we were told. We were living now for the moment—one moment, and only one, at a time. And these were monumental moments—moments that were off the clock and an eternity longer than they used to be, yet were never long enough. How long should the moment be, after all, when you say good-bye to your son? How much time should you get?

While they prepared for his transfer, we crouched down by Noah, who looked so small in that big boy’s bed, and we stroked his hands.

“Mommy loves you,” I sang quietly into his ear, noticing a trickle of dried blood and licking my finger to wipe at it.

“And Daddy does, too,” Andy said.

Our voices cracked along with our hearts. “I love you, Noah,” we said over and over, wishing he would wake up and push Andy’s face away, wishing we could laugh with him, wishing we could start this day all over again by returning to that creepy cabin and never leaving it again.

“You’re going for a helicopter ride, and Mommy and Daddy can’t come. Be a brave boy,” Andy instructed our silent, Saturday’s child.

We both looked at his broken body and forced ourselves to say words we didn’t know. Words we didn’t have. Words we couldn’t say.

Gathering the strength of my ancestors, I laid my lips against his ear and whispered, “You go and find Mimi. She’ll take good care of you. She always wanted a redheaded baby.”

Noah still had sand in his hair and saltwater on his skin from our combined tears and the ocean beyond.

“It’s okay,” Andy and I both lied to him. “You can go if you have to.”

And they took him away.

We staggered out to the waiting room where some of our tribal members had gathered.

“He’s gone,” Andy said and I cringed, hoping he hadn’t uttered an unintentional double entendre.

I realized I needed the bathroom. Cody and Diane came in with me. I waded across the room, numb and disconnected, collapsing on the toilet with the weight of the day pressing down on me.

“Look,” I said, realizing I had Noah’s blood on my hands and I didn’t even know where it had come from. But I clenched them into fists anyway and vowed to myself, I will never wash them again.

Then I shuffled over to the sink and washed them.

***

Andy and I managed to get back to the house to pick up our other kids so we could begin the long drive to Portland. All the kids had stayed with Bud and Marcella, and we returned to learn that Andy’s sister, Suzie, had shown up and had taken it upon herself to drive Cally to the sheriff’s office in town for questioning, and that for some reason she’d also taken Christiana with her—a classic nonsensical Suzie move. Cody was furious and flew off to rescue her own child. We were distraught but had a long drive ahead of us and had already wasted precious time going back to the house—we couldn’t backtrack yet another hour to collect Christiana. So we gathered up Hannah and Micah and had to leave without her, just one more thing to be upset about. Once I’d been forced to look up from Noah’s hospital bed, I wanted to glue the rest of my kids to my chest and never let them go. I desperately wanted Christiana to come with us, but I had to tear myself away and once again surrender to a reality I didn’t want. Now part of me was in the car, rushing to Portland, while another part was left behind, sitting in the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office, and yet another part of me flew away from me as fast as he could in his first helicopter ride.

Hannah, Micah, Andy, and I drove the three hours to Portland in silence and shock. The kids fell asleep, but I couldn’t. I felt like I’d been run over, but I would never use that particular figure of speech again and would cringe inwardly every time others did. I started to pray, but I couldn’t hold more than two or three words in my head at a time, resorting to simply, “Please, God,” and hoping He could fill in the rest. Neither Andy nor I spoke the entire trip, except for once when Andy answered a brief phone call from his brother and said, “That was Joe.”

Outside of our deathly quiet van, that promised sunny summer day proceeded as planned, only without us. We passed animals grazing and happy families sitting down to Sunday dinners, blessing their food and giving thanks to God for their good fortune. We were becoming different, apart, and separate, watching while others cavorted in the warmth of normality we had once relished.

How could they?

How could they eat?

How could they give thanks?

How could they frolic in the sun?

How could the sun conspire with all these strangers to magnify our cold, dark pain?

Why was this sunny day not meant for us?

It was all so cruel and so impossible to fathom. And we had to drive through it and watch. We had to hurry.

When at last we were crossing the Fremont Bridge over the Willamette River, the kids woke up. They stretched and asked where we were. I turned around and looked at my firstborn girl and boy, Hannah and Micah, reluctant to start this conversation.

“We’re almost at the hospital. I want you to know that Noah might not be okay. He might be paralyzed. He might be a vegetable.”

I was explaining this so badly.

“What? A vegetable? Do you mean like a carrot?” Hannah asked.

“Celery?” Micah added.

It might have been funny hearing them name the green and yellow vegetables I’d been counseled by my mother to eat every day had we been crossing over any other river on any other day, had our destination been any other place than our son’s bed at Emmanuel Hospital on the opposite shore.

But now we were pulling up to the door, and I failed to answer them, unable to add a new word to their young minds that would clarify the horrifying possibilities that awaited us on the other side of that hospital entrance.

Andy parked the car, and I dragged myself from the vehicle, stepping through the portals of the revolving door, which delivered us all with a swoosh into another realm. The four of us entered the hushed sanctuary of the children’s emergency room. Everyone tiptoed around in their silent shoes as if any noise would send us all right over the edge. The nurses greeted us with screaming solemnity and led us to a curtained-off room. They asked Hannah and Micah to wait on one side of the fabric barrier and then led Andy and me through to Noah’s side. Overwhelmed by relief to see Noah again, I allowed myself to breathe a bit deeper, inhaling the antiseptic odor of despair. Noah was hooked up to so many machines, but no alarms were going off, and that seemed good. His eyes were closed. I stepped up to look at him more closely but hesitated to touch him, afraid of disturbing something. I clenched my fists instead. Naked but for a diaper, his body was covered with all kinds of tape and tubes and gauze and monitors. I examined him from his feet up, slowly, as if I’d just delivered him, coming at last to rest on his head. Swollen. Way too big. Another terrible thing to see on a day filled with terrible sights.

The nurses and doctors looked at us with their professional pity and their carefully controlled selves while trying to make us understand that they’d kept Noah “alive” until this, the moment they were waiting for—our arrival. Yet another doctor entered our lives, introducing himself as the pediatric neurologist, and doing his best to get it through our thick heads that there was too much pressure on Noah’s brain and in his body. And no way to relieve it. Andy and I suddenly reverted from highly educated adults into people who couldn’t comprehend anything, who needed a lot of explanation, a lot of repetition, a lot of very simple words. The neurologist said that Noah had some other broken bones, like the arm he’d managed to reach out and touch me with for the last time.

My brain imploded.

Too much pressure? My head was filled with the same. Too much pressure. And no relief was in sight for me, either.

We may have attempted a few questions beginning with “Umm” or “What if,” but there were no question marks in this doctor’s mind. He had other lives to save, other parents to talk to. He was there to deliver a message and move on with his skills. He was a highly trained specialist who billed top dollar by the nanosecond. He was the deal-closer, the guy in the back room who makes all the important decisions. They’d kept Noah warm for our lips and our hands, for our farewell, and that was final. Period. They asked us if we’d like to donate his corneas, but I said no, not his eyes; I couldn’t bear to think of them snipping away at his beautiful blue eyes. The doctor concluded with the standard parting words that we would hear again and again, forever after. Words we didn’t want to hear. Words that spoke volumes but meant nothing at all and yet meant everything there ever was to say. Words that allowed others their exit: “I’m sorry.”

That simple phrase, those two little words, thus entered into our lives, replacing our son’s name. They would be spoken in hospital rooms and churches, and they would be mailed and handed to us disguised as flowers and food. They would mean so much and also so little. And sometimes, when we were most ready to hear them, they would be withheld. But that was all yet to come.

Right now they meant that Noah wasn’t coming to the beach with us or to the lake with us, or even home with us that sunny summer day. Or ever again. I remembered Noah’s outstretched hand as we headed for Hootenanny without him just last night, and his pain at being abandoned by us socked me right in the gut. Now that I was the one left behind.

Noah was already gone. He had left without us. We had told him he could.

The nurse appeared and said, “You can bring the children in to say good-bye, but maybe they’ll just want to touch his foot or hand.”

I guess she thought maybe they wouldn’t want to see Noah’s head all big like that. But we had lost our ability to speak and so gave them no warning. Hannah and Micah, Noah’s brave big sister and brother, were having none of that, anyway. They marched right up to their No-wee’s bed and climbed aboard. Hannah caressed his face. Micah kissed his cheek. They talked to him. They loved him in the way they had loved him since the day he was born. One last time.

The nurses asked us all to wait on the other side of the curtain while they silenced the beeps and whirring of all those machines and what was left of Noah. Andy and I hugged each other and covered each other with the tears of the “be” people—the bewildered, the bereft, the bereaved. I soaked the shores of Andy’s shoulder with the first waves from my ocean of grief—me, who hated to cry. And while I cried my heart out, I could see the nurses through a gap in the curtain working to disconnect our baby, our son, our Noah. I watched them removing all that tape they’d so recently covered him with, adhering Noah to the earth until our arrival. Now his family was here. Now they could detach all that held Noah’s body here with us. With each pull of the adhesive, they wrenched him away from us. With each rip, each tear, each tiny blond hair they pulled from his body, my own heart ripped and tore. I watched until they unhooked Noah from the question marks of the present and placed him firmly, finally, in the past. Until nothing was left but the sounds of their footsteps.

The nurses called Andy and me back in. They wrapped Noah’s body in a blanket and handed him to me like he’d just been born. It was 6:15 p.m. They ushered us into a quiet room with a minister we didn’t know and who could offer us nothing if not a miracle. I sat down in a Papa Bear–size wooden rocking chair that made me feel small and inadequate, automatically adjusting the body of my baby in the football hold as though we were preparing to nurse together for the first time instead of rocking for the last. I held him and looked down at him. And then I stopped rocking. This was not Noah. He wasn’t there. It didn’t feel like him; it didn’t smell like him. And I knew immediately, right then and there, that this was only Noah’s body. The body Andy and I had created out of our love for each other. The body I’d grown inside of me and pushed out into the world only fifteen months prior. The body I’d nursed from my own every day. The body Andy and I had cuddled and tickled and bathed and fed and walked and sang to and pushed on the swing so many, many times. The body we’d all loved and cared for. The body that was broken. I felt nothing. Noah was gone. And I did not want to hold this shell of him any longer. I handed him to Andy.

“This is not Noah,” I said.

Andy cradled his son’s body in his long arms for a moment and agreed, “No, it’s not.”

We looked at each other with wonder as Noah taught us both in that moment that we are not our bodies. They say the soul weighs twenty-one grams and we both felt its absence. We held his body but not his soul. Noah was not in that room.

We went back to the treatment room and laid Noah’s body on the bed. The kids came in.

“Can I give him his first haircut?” I asked.

The nurse handed me a pair of scissors, and I cut some of the strawberry-gold locks off the head of my dead baby. Then I rinsed off the traces of blood and sand in the sink, the cold tap water mixing with my warm tears. The faceless nurses handed us a bag with Noah’s torn, dirty clothes, his saltwater sandals, and a souvenir from his short visit—one bright-green, wrist-size Oregon Trauma System bracelet and a card with his dead handprint on it, slightly smudged. There was nothing more we could do, and we were made to understand that standing there forever was not an option. Somehow we gathered the will to turn and take that first baby step away. Away from our baby. Never having been away from him for more than a few hours, we stepped away from him forever.

The trained professionals who were still thinking logically brought me back to the present, asking, “Do you need to call anyone?” Before I could answer, I found myself seated at a desk with a phone receiver in my hand. I dialed one of the few numbers I knew by heart. “Mom,” I said, taking a deep breath, “Noah is dead.”

I immediately wished I could snatch those three words right back and clasp my hand over my mouth so as never to let them escape from my lips again. I could feel my mother’s smile collapsing in horror through the receiver. I could hear her mind spinning, trying to deny the words she thought she’d just heard. I would have countless future experiences of wanting to spare others from the news I had to share. Over time I would learn how to break it to them gently. Over time I learned to comfort those who wanted to comfort me. But this time was the first time. I was brand-new to this—the speaking of the three short words that would make this all forever real.

I don’t know how much I told her. I don’t remember the rest of the conversation, the details, the questions, the future plans. We had no future plans. I know that when we finally hung up she was faced with telling this terrible news to my dad and my older brother, Brian, and his family and their friends who were all visiting. She, in turn, destroyed the peacefulness of their fine summer evening while they rocked on the porch listening to the frogs and loons calling happier news across the lakes to each other. Noah had played in those same lake waters one month earlier. He had skimmed across them happily in boats, big enough this summer to enjoy his Mickey Mouse life vest. He’d slid down an orange plastic Little Tykes slide at the beach, landing bravely with a splash in the waters of his ancestors, laughing. But the places that knew him would know him no more.

We limped down the hall through the pediatric ICU, too numb to wonder if that would have been a better place for our son. The revolving front door pushed us back into that same sunny day, still relentless in its intent to shine brightly for everyone else. We shielded our eyes and limped along, even sadder and more broken than when we’d arrived. All hope for a happy ending was sealed by its final swoosh behind us. We managed to find our van, and Andy unbuckled Noah’s car seat and moved it to the back so Micah and Hannah could sit together, even though they didn’t ask, didn’t fight over it. I hoped Christiana was on her way home with the Martins but didn’t have the wherewithal to call and find out. We drove the hour home to Salem, beginning to test the replay button of this most terrible day, daring to search for the highlights and begin to comprehend.

How on earth could God have been so unavailable to us on a Sunday morning at ten o’clock? Surely that should have been a safe moment for us, when the power of the Holy Spirit moves among us, and our God, who is an awesome God, draws nigh for just a closer walk with thee? Ten o’clock, the time when our church service began, when I’d normally rush in to sit in my favorite pew after depositing my children in their respective Sunday school classrooms to learn about Jesus, after prying my little boy’s clutching hands from my Sunday dress and extricating myself from the nursery with a smile and a promise. “It’ll be okay, Noah, Mommy will be right back.” Or so it would have been—that is, if I hadn’t left Salem and gone to the coast to help my mother-in-law, skipping church that day.

Our absence had violated God’s commandment, “Remember the Sabbath and keep it holy.” Was this our punishment for skipping that one little commandment? One out of ten wasn’t bad, was it? We hadn’t spent the day taking the Lord’s name in vain or coveting our neighbor’s ass or stealing or bearing false witness or carving miniature idols out of wood. Given the opportunity, we could even have argued that we were actually obeying the commandment to “honor your mother and father,” which surely extends to injured mothers-in-law as well. But we’d had no opportunity to mount a defense, cut off as we were from God’s mercy, our verdict delivered with terrible finality.

I thought about God as Andy drove down I-5 from Portland to Salem. And I thought about Jesus. And in light of my day, I thought about them both in a whole new way. When Jesus died, he returned to the heavenly home of his Father and dwelt with Him there, forever seated within His reach at His right hand—I’d memorized and mumbled this creed so faithfully at all the Saturday night masses of my youth. But now I wondered, so just how terrible was Jesus’s death, really, for God, his Father? Because when my son died, he was taken from me so suddenly and finally, that all I had left within the reach of my right hand was the smell of his clothes and his blood on my hands and the toothbrush he’d used and the toys he’d loved to play with and the indent from his head on his little white pillow embroidered with his name, NOAH, which we’d all clutch desperately and soak with our tears for many months to come. And I had his brother and sisters, who’d ask, “Where did Noah go, Mommy? Where is he now?” as I clenched my empty fists and searched for answers to tell them.

God isn’t always merciful. Sometimes He doesn’t even pay attention. Make no mistake about that. And because we’d skipped that sanctuary visit on Sunday, we found ourselves doing a most unimaginably cruel penance there, five days later, on Friday: burying our son.”

Today is December 5, 2018 and I’m finally finishing this essay I began over a year ago. Today is also a national day of mourning for the death of our 41st President, George HW Bush, so this seems a fitting thing to complete on this day. Just as we keep track of our children here on earth, so I keep tabs on heavenly happenings. George was preceded in death by his wife, Barbara, only a matter of months ago but also by their daughter, Robin, who died many decades ago at age 3 from leukemia. I hope they all now know my son, Noah. It goes without saying that some day I, too, will die. And even though I’ll be sad to leave my loved ones here behind, still, like George, I’ll be reunited with my son, Noah. And what a happy reunion that will be.

Kelly Kittel (Noah’s mom) is the author of the award-winning book, Breathe, A Memoir of Motherhood, Grief, and Family Conflict and has also been published in numerous anthologies and magazines. www.kellykittel.com

Donate in Honor of Noah